“The Arte Público Press created an outlet for Latinos, especially during the civil rights movement, which was something that was inevitable because we were striving for independence in every direction of every single way.”

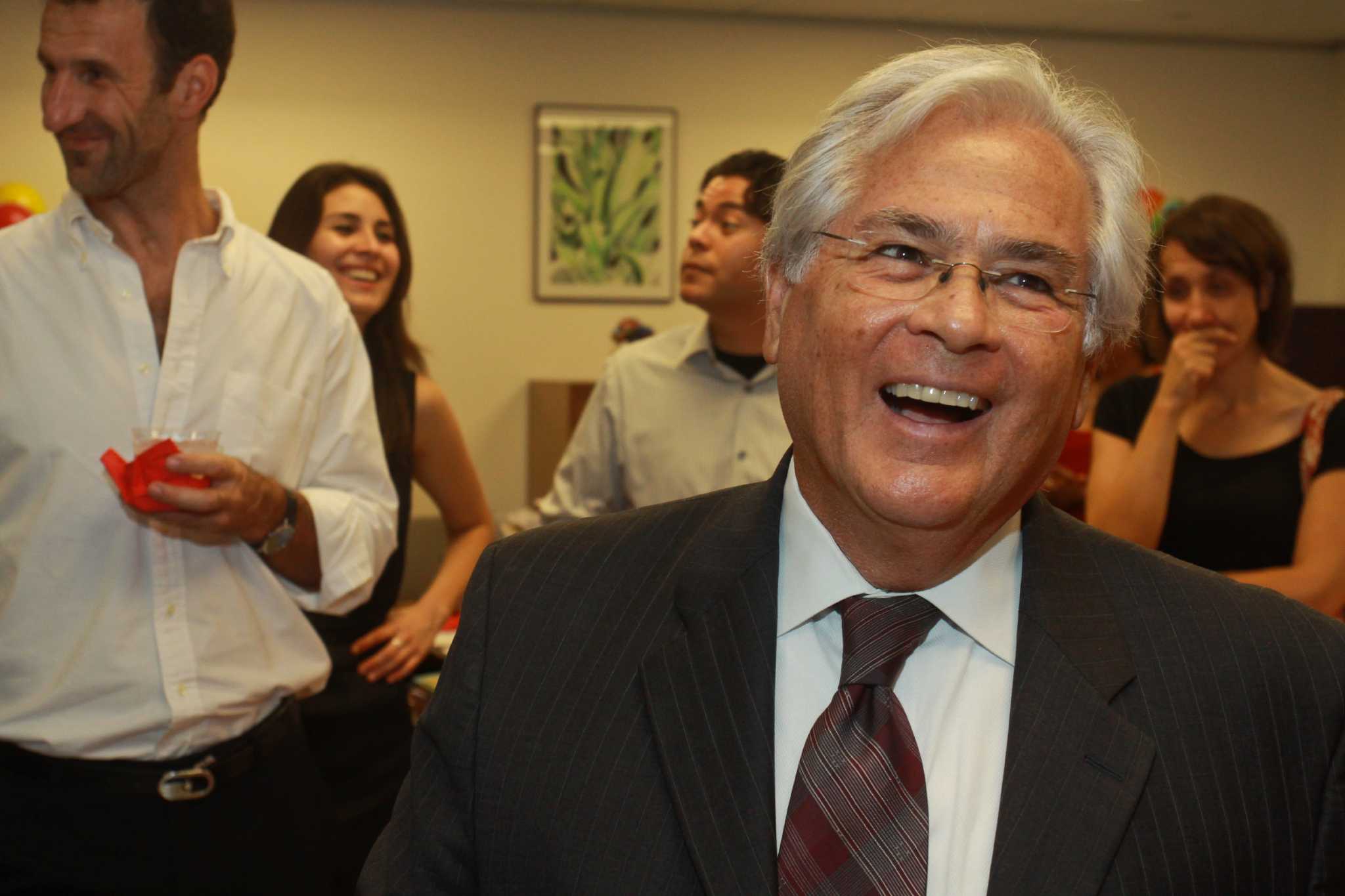

-Dr. Nicolás Kanellos

Arte Público Press, publisher of Latino literary creativity and arts, is the nation’s oldest and largest publisher of U.S.-based Hispanic authors. Founded in 1979 by Dr. Nicolás Kanellos, Arte Público Press has shone an incredible spotlight on Latino voices and provided a much-needed platform for their success and publication through the intellectual space at the University of Houston. The Press was the original publisher to many literary revolutionaries like Sandra Cisneros, Luis Valdez, Victor Villaseñor, and Helena María Viramontes, and they have done extensive philanthropic work to promote young voices and literacy. On their 40th anniversary this January, Arte Público Press received the prestigious Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award given annually to a person or institution with great contributions to book culture, with past recipients including Margaret Atwood and Pulitzer-winning Toni Morrison. This award is monumental, and we would like to share an interview with Dr. Kanellos regarding the award and Press’ accomplishments.

An Interview with Dr. Nicolás Kanellos

WLT: You started Arte Público Press in 1979 during the Hispanic Civil Rights movement to showcase Latino voices especially because mainstream media did not publish their incredible works. What value do you believe that writing and the creative arts bring to a person, and how has your press been able to emphasize these values of creative expression for the Latino community?

Dr. Nicolás Kanellos: Ever since human beings walked the planet on the earth, expression has been very important and became elevated to the level of art very early in human history. What we have found, going back to the civil rights movement in the 1960s for independence, is that with no creative outlet, it’s like putting a stopper on a bottle of gas, just building up pressure until it must be released. The Press created an outlet for Latinos, especially during the civil rights movement, which was something that was inevitable because we were striving for independence in every direction of every single way. Second, the creative arts–theatre, music, literature–became just as much a part of the civil rights movement as voting, political organizing, marching, boycotting, etc. At first literature, theatre, and music were used to support these movements as secondary to the politics, but by the end of the 1970s the creative arts were liberated from just serving political ends and became independent endeavors. In fact, the poets were the ones who would kick off a march, support a boycott and verbalize what people were feeling during the whole movement. We were on the same page and were aware of all these creative people not getting much of an outlet, which is why we started our magazine in 1973 and created the Press in 1979.

WLT: What benefits do creating an exclusively Latino platform bring to the Latino community? And also, have you faced any setbacks because of the platform belonging to one group?

NK: We named ourselves Arte Público Press because we saw ourselves as part of the public art movement which meant that we would be drawn to the community, from public spaces, and reflect it back just like a mural reflecting the Latino community’s life. We thought that our literature should be drawn from the community, its languages, its themes, its perspectives, its visual culture, and reflect that back to the community by making our books available to the community and not just the grassroots. The importance of that, why we continue to do that, is because there is still very very few opportunities for Latinos to publish their works. You pick up an issue of Publisher’s Weekly and quite often, of the 50 or 60 books reviewed each weeks, there are weeks you don’t even find one book written by a Latino. You pick up the New York Times book review and you often won’t find anything by Latinos. The doors are still very closed, though there are exceptions that go through the creative writing pipeline or other publishing houses, but still, writers outside of the institutions who did not go to elite colleges, don’t have that much of a chance. We still have a role here, and the drawbacks are that we are a minority organization and a minority community, and we are treated like such. Automatically, Latino creativity is seen as something marginal, unprofessional, untutored; all these stereotypes are natural, and we are facing them. When we put our books out there, there are librarians and teachers going over every piece we work, and looking at how well we write English.. It’s that kind of response we often get: not seeing our books reviewed, not being eligible for any awards, that’s the response we get. So getting this major award, the major award for publishers, will hopefully help us break through to get more of our books and writers recognized.

WLT: The Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement award is such a huge prestige and given annually to a person or institution with an extensive history of significant contributions to book culture, which is often often authors. You received this award as the director and founder of the Arte Público Press; what was your initial reaction to this great honor and what did it mean to you all?

NK: Well, to be honest, I cried. It took me completely by surprise, it was like a bolt of lightning coming out of nowhere, I hadn’t even aspired it to that. It’s only the fourth time they (National Book Critics Circle) have every given it to a publishing house, so it’s something that was never even on my horizon. The initial shock, surprise, happiness, was very emotional for all our staff, and so was going up on the stage with the staff to receive the award; they have been with us about twenty years or more, and we are all in love with the mission. We work very hard, over forty hours a week, and we put all our efforts into publishing and promoting the writers and books, though we do not promote the Press. We’re an unknown entity, even in our hometown; we are called one of the best-kept secrets because we are not helping or marketing ourselves, we’re marketing our writers and books.

WLT: Given all the hard work you and the Press staff put in, which accumulated in this great award, to what do you most attribute your Press’s success?

NK: We have to mention, as part of our success, our writers and the books that they have written, which have become bestsellers, and we’ve launched the careers of many writers that have gone onto big publishing houses. The publishing world know where these people came from; it wasn’t from agents or other publishers, they came from us. We are out there scouting at book festivals and community organizing, and we recognize people doing good work and invite them to submit their books. We get 2000 submissions a year and only get to publish about 25 books a year. Unlike other publishing houses, we go through all the submissions, and we find gems. In the case of Sandra Cisneros, she was working at a high school in Chicago with at-risk kids and capturing the lives and stories of these students; she’d read these stories at open mics and writer gatherings, so I invited her to put these stories together and submit to us. We worked with her to form it into a book, The House on Mango Street, and it was wonderful. At first, nobody knew about it, but we raised money to tour the authors around small libraries and convincing professors to let the writers come meet, and so Sandra, Evangelina Vigil, Pat Mora, Helena María Viramontes, all became recognized and known in academia. It wasn’t until a few years later, when Stanford and elite institutions integrated the curriculum and started picking up our books, that the rest of the world began to take note. And quite often, that note was negative. The Wall Street Journal had a headline about us–great books replaced by the not-so-great, they were talking about our books. It had a wonderful effect actually, the opposite of what they wanted because people started wondering what these books are. People went to bookstores that didn’t carry our books, so we began to get more orders to be shelved and took off from there.

WLT: I see that you left teaching at Indiana and accepted an offer at the University of Houston in 1980, where you led much of the efforts for Arte Público Press. How does the Houston writing community compare to other communities and how has it helped the Press gain the momentum it did?

NK: Houston, out of Texas, is probably home to the most dynamic writing community because you have grassroots writers from diverse communities in the most diverse city in the country. You have Asian American, African American, Latino, Anglo American writers quite often performing at the same venue. We have many community-based writing organizations like Imprint for national writers, and Nuestra Palabra, which is a Latino grassroots writing organization that has a radio show and does presentations of local writers. We take writers across the country touring and into the schools, which is supported in part by the Texas Commission on the Arts. We have programs with the Houston Public Library, and Houston has two major creative writing programs at the University of Houston in the English and Spanish departments. We have one of the major literary bookstores in all of the Southwest, Brazos Books, that has open doors to everyone with an active reading program that has had quite a bit of impact. A lot is going on Houston.

WLT: Issues like the word gap in low income communities with children not receiving the same vocabulary or exposure to certain words impact their outcomes greatly, and especially being raised in non-English speaking households can affect how children perform on standardized testing. Your Latino Children’s Wellness Program among other initiatives is incredibly impactful on such children’s lives. How have these communities particularly benefited from your program and what future do you hope it creates?

NK: We have our Pinata Books imprint which has children’s dynamic picture books, middle reader books, and adult books. We have a program with the Houston Independent School District wherein we take a librarian, writer, and one of our staff people and go into a school to work with parents where we teach them how to support their children’s reading, create a reading culture at home, and show them how books work and how to read to their kids. They’ll give everybody a library card, a handout, and five them children’s books for them to take home. Quite often they’re the first books these children ever own. We bring in writers to talk about the importance of creativity and writing and how they became writers as well as teach them to tell their own stories. Our program goes beyond reading to kids, we are more involved because, oftentimes, these kids have never seen someone who looks like this and published a book.

WLT: As a final question, what has been your favorite moment with Arte Público in the past 40 years?

NK: What gives me the greatest joy, is when I’m in the schools and I see the kids holding the books and reading them and loving them. I love when I’m there, and the kids will come around and hug you and want to hold onto you because they’re just so overwhelmed. That–that’s my best moment.

—

Thank you, Dr. Kanellos, for your inspiring work!

To find more about Arte Público Press, click here.